Subscribe & stay up-to-date with ASF

Joan Wulff, the grande dame of American fly-fishing, is someone who needs no introduction. But we’ll give her one anyway because, well, she deserves it.

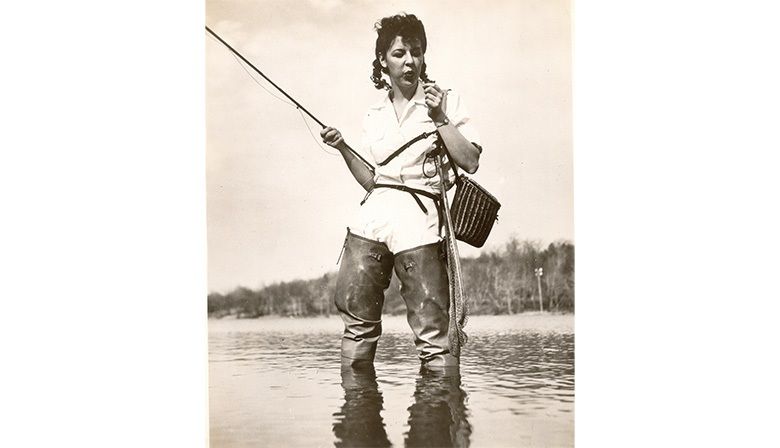

Joan grew up in New Jersey. When she was five years old, her parents took her to Greenwood Lake to ride along as they went fishing. She watched her father blissfully cast his line into the lily pads for bass as her moth-er laboured behind the oars of the boat. That was the moment, Joan says, when she realized, “I wanted to be the fisherman, not the rower.”

But it would take some time. Her father, hewing to the mores of the time, frequently took her brothers to the water, but never her. One day, she asked her mother if she could try her father’s rod. Her mother said yes, and Joan promptly lost the tip of the two-piecer. “It went down in six feet of water,” she says. The man who lived next door happened to get home earlier from work than Joan’s father, and he helped retrieve the rod piece with a rake “and saved my mother from being reprimanded,” Joan says. Joan’s father, realizing Joan’s enthusiasm, then began to take her to the cast-ing club with her brothers. And from thatpoint on, Joan never stopped fishing—nor helping to change the image of an entire sport.

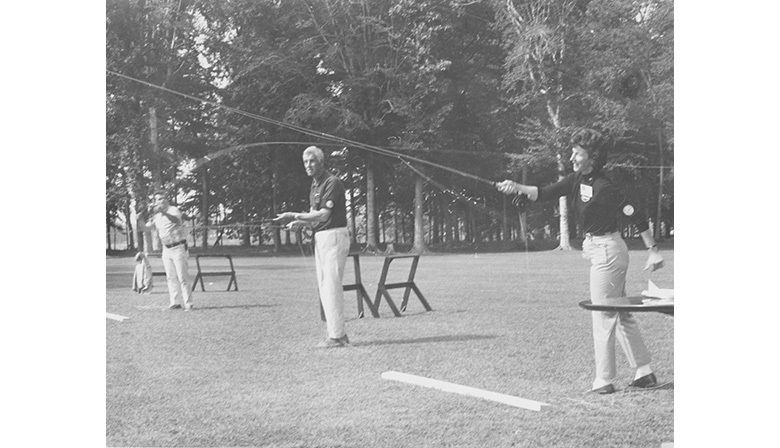

She took a particular liking to the fly rod—the casting action naturally appealed to her uncanny sense of movement and body control (she is tall and graceful and was a dancer as a child and later a dancing instructor). By the age of 12, she’d become so adept at fly-casting that she entered a local competition … and won. As she got older, she began to enter national fly-casting competitions and won 17 titles from the early 1940s until 1960. In the 1951 competition, there was no 9-weight distance event for women (not enough people had signed up). So Joan was placed in the men’s division… and won.

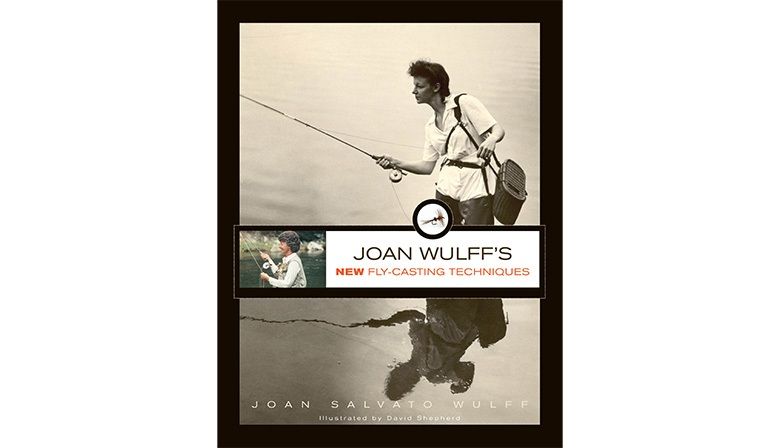

In 1967, she married Lee Wulff, and the two of them set off across the globe, fishing, promoting fly-fishing and having a blast. “We spent 24 hours a day together,” she says. “True soul mates.” In 1979, the duo founded the Wulff School of Fly Fishing on the Beaverkill River in the Catskills, introducing legions of new anglers to the sport. Joan, in particular, became known as one of the pre-eminent casting instructors in the country. She authored four books based on her techniques and starred in a few instructional videos. (One of them, Joan Wulff’s Dynamics of Fly Casting, has sold more than 50,000 copies.) She con-tinued to teach and fish all over the world with Lee until his death in 1991. She later married Lee’s friend, environ-mental lawyer Ted Rogowski, and they, too, fished until he passed away in 2021.

But maybe more than anything, Joan was a pioneer, the person most responsible for opening up the sport to women through her instruction, books, videos, conserva-tion work and general ambassadorship. (Joan was trustee of the International Game Fish Association as well as a U.S. director of ASF.) The results of her labour are now seen on rivers and flats all over the world, as the sport has continued to attract more and more women. “Casting a fly is inherently feminine,” Joan once told me. “The unrolling loops are like musical notes held and drawn out. When you cast, you’re attached to the weight of the line, you’re con-nected. It’s beautiful.”

I recently caught up with Joan, now 95 years young, at her home on the banks of the Beaverkill to talk about Atlantic salmon, her legacy and how she fishes now.

Monte Burke: I’ve always wanted to know about your first Atlantic salmon trip. Could you tell us a bit about it?

Joan Wulff: After I married Lee in 1967, we went to the Miramichi together. And on my first day there, I caught my first salmon, a beautiful nine-pounder [four kilograms].

MB: That’s pretty amazing, a salmon on your first trip.

JW: It’s not that amazing when they put you where the fish are!

MB: And you guys kept salmon fishing from then on, right?

JW: We did. My favourite river is the Upsalquitch, at Two Brooks, the camp that was owned by Joe Cullman. He used to have us up every year and I kept going up with Ted.

MB: What was it that you liked so much about Two Brooks?

JW: Well, I liked the challenge of the steps from the river to the lodge, of how long it took. I’d count the 67 steps as I walked up them. We got to know the river so well there, the maybe seven pools. Each year, we got to know them better, to the point that when a pool name was mentioned, I would be able to think of a particular fish that was caught there. The camp was so comfortable, too, and there were always new guests every year, so we got to meet interesting people.

MB: How about some other interesting places that you fished for Atlantic salmon?

JW: Well, I loved them all. I’ve fished the Miramichi a lot. I fished all over the place. New Brunswick, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Scotland, Russia, Norway. I covered some great water. I wish I could have fished more. I was always unhappy that I wasn’t a man back early in my life, because I could have spent more time fishing. No matter what men said then, they always had more opportunities to fish, more often and for longer periods of time!

MB: What is it about Atlantic salmon fishing that hooked you?

JW: It was because Lee made it all sound so romantic. The fish going out to sea and coming back and having to wait to spawn and then hunkering down during the winter while waiting to go back out. It’s just a romantic story. That always stuck with me and was a big part of what made it so compelling.

MB: Do you have one fish that was most memorable, one that you landed or one that you lost?

JW: It’s funny, the one that jumps to mind is one that landed itself. I hooked a salmon once on the Restigouche that, as I was playing it, suddenly swam into shore below me. It didn’t totally beach itself and go dry, but it stayed in the really shallow water and I walked down and just reached down and released it. It was a 12- to 15-pounder.

MB: How do you approach a pool when fishing for salmon?

JW: It’s all about covering the water. I always started short with my casts and then added a couple of feet [0.6 metres] as I worked my way down the river. I did it all very carefully, trying to give the salmon every chance to see my fly. And I wasn’t one of those people who changed the fly a lot. Covering the water was more important. That’s worked well for me.

MB: Prefer fishing a wet or a dry?

JW: I prefer dry fly–fishing, but I always waited until a salmon showed itself before I tied one on. And I always hoped one would show itself because I really enjoyed fishing with a dry.

MB: Favourite fly?

JW: All of Lee’s favourites. I loved the Wulffs for dries and the Lady Joan for a wet fly. And the surface stonefly was effective because it was something the fish didn’t always see. I loved the Prefontaine as well. In Lee’s last five years of fishing, that was the fly he used all the time. I loved that it skated. After you go through a pool a few times and nothing happens, you have to think of something, and that was always good to try.

MB: Besides Atlantic salmon, do you have another favourite fish?

JW: Of course.

MB: Like?

JW: Tarpon. And I would love to say permit, but I never got to spend enough time fishing for them to really figure them out. I told Marshall Cutchin [the former saltwater flats guide who runs the fishing newsletter MidCurrent] that in my next life we have a date to do some real permit fishing.

MB: The sport of fly-fishing has evolved so much during your lifetime, especially when it comes to the huge—and still growing—number of women anglers. That must be pretty satisfying for you to see.

JW: Well, I think Robert Redford in A River Runs Through It played a huge role. After that movie came out in 1992, we had more women in our school than men for 12 straight years. Whenever I’m given credit for getting women into the sport, I say, ‘No, it was Robert Redford.’

MB: You both did your parts!

JW: I’m just so happy that so many women are fishing these days and becoming guides and professionals in the fly-fishing world. I’m delighted that I have lived long enough to see it. It took a while.

MB: What’s one key thing you learned during your fly-fishing career?

JW: It had to do with analyzing the cast to try to make us better instructors. When Lee and I first started out, instruction was all about ‘watch me and do it like this.’ That put the burden on the student. With the school, we changed that by analyzing the cast and being able to talk to the student about certain moves, not just ‘watch me.’ That gave me a real passion for analyzing and presenting casting to people who wanted to learn. I’m not sure how casting is taught now, but I hope they are using my loading move, power snap and follow-through, which were the three terms I used to describe the physical movements.

MB: You’ve played an outsized role in the world of fly-fishing as a caster, an instructor, an author, a conservationist and a pioneer. What has the sport meant to you?

JW: It was always something bigger than I am. The conservation, the people I’ve met—who are the best people in the world—the places all over the world it’s taken me. I’ve been rewarded by the sport.