Just at the foot of the rapids below the dam was where records indicate the last salmon were seen. There were also occasional unconfirmed stories of salmon being spotted even after the dams went up. Is it possible salmon kept returning to the river well into the 20th century?

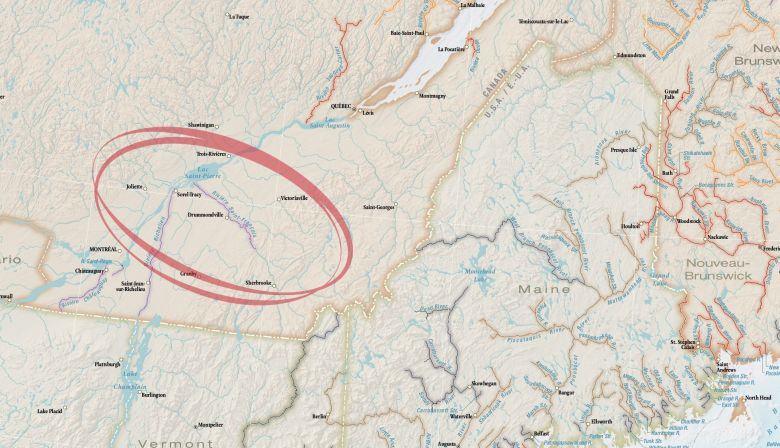

Allard had told me that as recently as the late 1990s, his group had succeeded in obtaining a few thousand smolt from a laboratory study, which they released in the river near Sherbrooke, Quebec. It’s far-fetched, but if they had spawned and their offspring had returned as adults, maybe they could have found suitable habitat in the St. Germain River, a large tributary that empties into the Rivière Saint-François below the dams.

I was fortunate to interview Yvan Gosselin who told me another story of a “guerilla” salmon stocking in 1988. At the time, Gosselin was a biologist and also a ringleader among the dedicated group of Drummondvillagers who had dedicated themselves to bringing salmon back to the Rivière Saint-François . Frustrated by the obstacles put up by various government agencies, Gosselin and his band of dreamers arranged to get broodstock from a hatchery near the Port Daniel River on the Gaspé Peninsula. They spawned these fish and hatched out a few thousand fry. Then, before the cameras of local media and an audience of curious onlookers from Drummondville, they released the parr just below the dam at the Lord’s Falls.

“I was following a dream, and it wasn’t just me,” Gosselin told me. “We felt an energy back then, a flame, that still hasn’t burned out to this day.”

Allard and Gosselin hoped that perhaps a few fish would find their way back up to these very falls. Dreams can be contagious, and I seemed to be having a daytime version nowcatching one. I walked closer to the riverbank half-hoping I might see a salmon leap. Out of the corner of my eye I spotted something. No, not a salmon, but what looked like … like … yes, a sign! It was a historical plaque partially hidden by trees and shrubs. I wasn’t dreaming about this.

Allard joined me, happy to have found his sign, but our joy was short-lived. The plaque was a tribute to the construction of the two dams. In part it read, “All through this century the river has played an essential role in the economy of Drummondville.”

But near the bottom, almost as an afterthought, the historian who prepared the text had added: “However at the same time, the river lost one of its principal riches, the large quantities of salmon that it held diminished rapidly and were soon completely disappeared.” These last lines were in large type and bold, as if the graphic artist and historian conspired to draw attention to the loss. Could it have been Yolande Allard or Serge? When I asked him, he only smiled.

As we left, the thought occurred to me that there should be another plaque, with a photo of a leaping salmon. It would read, “You don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone.” Just ask Serge Allard and other members of the SSSF. For them, the disappeared salmon run is like a hole in their hearts, one no medical team can repairsomething for which no simple cure has been found.

But that won’t stop them from trying.